On Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his Chain of Light

On Nusrat's death anniversary, resident Qawwali expert Musab looks into what made him, preparing us for an upcoming release of unheard Nusrat recordings.

At legendary film director Ernst Lubitsch’s funeral, his one-time screenwriter Billie Wilder remarked to William Wyler, “Alas, no more Lubitsch”. Wyler is said to have replied, “Worse than that, no more Lubitsch films”. As an elder millennial who remembers the passing of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, I felt a similar thought crossing my mind on 17th August 1997, when all the newspapers in Pakistan carried the news of the great Qawwal’s passing on their front pages.

It’s some consolation to 11-year-old me, and to Nusrat’s countless admirers across the globe that twenty-seven years after his passing, unreleased recordings are still being unearthed. The latest, an album titled Chain of Light is scheduled to be released on 20th September this year. The story of the album’s recording at the time when Nusrat was first gaining popularity across the western world, and the international excitement elicited by the news of its release, led me to look back on my own (almost) life-long obsession with the man and his music.

For those of us who grew up in the nineties, Qawwali was a ubiquitous part of the Pakistani musical landscape, constantly playing on TV, radio and across the tens of millions of cassette-tape decks across Pakistan. I’ve written earlierabout how my parents’ car stereo was the source of my musical education, and no childhood road trip was complete without the latest Nusrat release. During the mid-nineties, Nusrat’s releases included traditional Qawwali, ghazals, geets, milli naghmas, film and TV soundtracks that became an indelible memory for everyone of a certain generation. He was, for the five to six years preceding his death, the monarch of all he surveyed, lauded in his homeland as well as abroad, an undisputed giant of music. The suddenness of his passing was an immense shock, as none but his closest circle was aware of the terrible state of his health in the last years of his life. Nusrat’s death at 48 years of age not only robbed his fans and admirers of a voice that was an integral part of their lives, but also robbed the world of an artist who was at the peak of his creativity and artistic powers.

I remember talking to a Qawwali afficionado a few years ago, someone who had organized Nusrat’s mehfils at various Urs celebrations across Pakistan, and who had been closely acquainted with a number of Qawwals and traditional musicians. I expressed the same sentiment to him, that Nusrat had gone too soon, that he had years and years of artistic creation ahead of him, and that it was a shame that the world was robbed of the chance to experience more of Nusrat’s creative genius. My friend’s reply was unexpected, and the more I think of it, quite profound. He agreed that Nusrat had indeed passed too soon, but he added in his Lahori Punjabi accented Urdu, “Khan sahab ne ek din bhi zawaal ka nahi dekha” – “Khan sahab did not face a single day of decline”. Nusrat died at the zenith of his popularity, capping a lifetime of ascending – sometimes against great odds – the ladder of success and acclaim. While his rise may appear meteoric twenty-seven years after he passed, it was anything but. For me, the years of Nusrat’s growth and development as an artist have always been the most fascinating ones, filled with stories that form essential milestones in his ‘superhero origin story’.

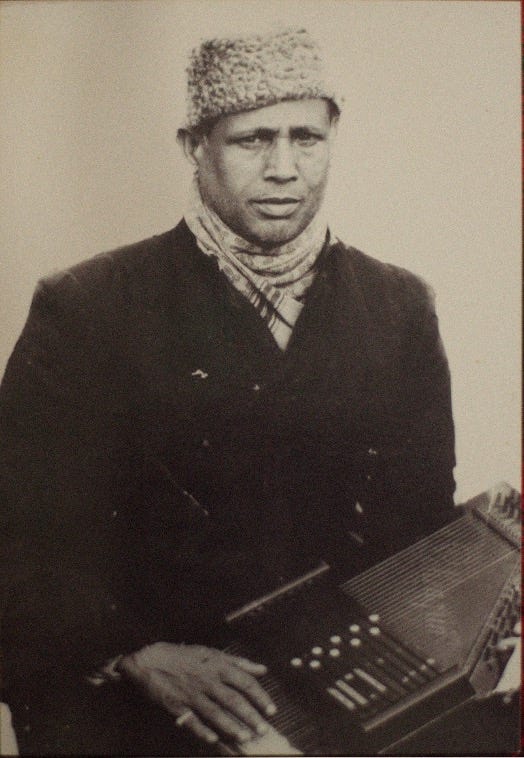

From the mid 1920s till Ustad Fateh Ali Khan’s death in 1964, the three brothers Fateh Ali (1901-1964), Mubarak Ali (1879-1974) and Salamat Ali (died 1983) were the pre-eminent Qawwals of the first half of the 20th century. Popular among the masses, classical music afficionados as well as Sufis, the three brothers were the most popular Qawwali performers in the subcontinent, featuring regularly on radio before and after independence. During partition, the family migrated to Lyallpur (present day Faisalabad) where Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was born in October 1948. Initially named ‘Pervez’, his name was changed to Nusrat at the direction of a Sufi, who suggested that a change of name would prove auspicious. Nusrat’s father was a renowned Ustad who had several qawwals as well as classical musicians as his students or ‘shagirds’, however, he was reluctant in teaching music to young Nusrat, hoping for a career in medicine rather than music for his only son. Nusrat’s curiosity about music led him to repeatedly eavesdrop on his father while the elder qawwal used to train his students, invariably getting caught and receiving a scolding. Eventually, after multiple scoldings and an appeal by his mother Nusrat was accepted into training. Initially, he was taught the tabla by his father and uncles, who thought an early grounding in the intricacies of rhythm was essential for a budding musician.

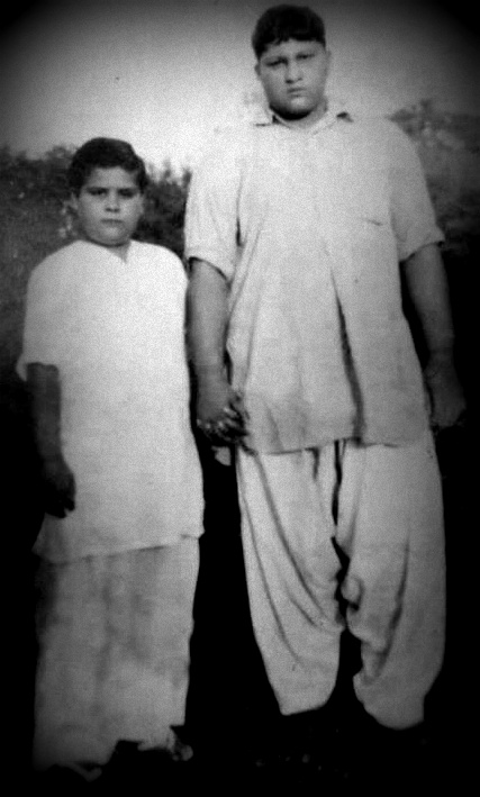

Ustad Fateh Ali Khan passed away in 1964 after a brief battle with cancer, leaving his family’s qawwali party and his young son in a state of shock and despair. Nusrat and his brother Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan were barely in their teens, while their uncles Mubarak Ali and Salamat Ali were octogenarians, leaving the fate of the family’s six-hundred-year-old legacy as Qawwals in the balance. Both Nusrat and Farrukh Fateh Ali Khan have spoken about the gloom that descended on the family and the qawwali party, and the fear that 16 year old Nusrat was absolutely unprepared to take on his father’s mantle. The first test for young Nusrat would be his father’s ‘chehlum’ – the fortieth day after his passing, which is traditionally the day a traditional classical musician’s successor is announced with the tying of the ceremonial turban or ‘dastaar’. The events of the next forty days were described by Nusrat as a ‘vilayat’ – divine guardianship. A few days after his father’s death, Nusrat had a dream where he was taken by his father to a large shrine, a shrine that was unknown to Nusrat, and was instructed to sing. In the dream, Nusrat prevaricated that he didn’t know how to sing. But after his father’s insistence, he opened his mouth and found himself singing, and he was still singing when he woke up a few minutes later.

A few days later, the family received a letter from the shrine of Hazrat Moinuddin Chishti (RA) at Ajmer –the shrine young Nusrat had seen in his dream – announcing that the guardians of the shrine had received a premonition that Fateh Ali Khan’s mantle was going to be passed to a worthy successor, his son. Nusrat’s uncles, emboldened by these events, devoted themselves to training the young orphan, and their efforts paid off when Nusrat gave his first public performance at his father’s Chehlum ceremony, silencing naysayers and reassuring his family of the future of qawwali in their gharana.

What followed was a decade of intense apprenticeship for young Nusrat, as he joined his uncles in the family Qawwali party, getting an on-the-job grounding in the intricacies of classical and qawwali music while regularly performing for Radio Pakistan as well as various mehfils. This is the era where Nusrat’s phenomenal natural talent first began to shine, and he was promoted from accompanist to the leader of the family qawwali party. His uncle Ustad Mubarak Ali Khan, now in his nineties, resumed the role of second lead that he had been occupying for the previous half century. The few recordings from this era are remarkable, as the young Nusrat’s maturity, technical prowess and musical artistry is on full display. Even as a youngster in his early twenties, Nusrat’s voice commands immediate attention and foretells the future.

Nusrat’s uncle, Ustad Mubarak Ali Khan passed away in 1974, leaving Nusrat in charge of the qawwal party, accompanied by his cousin Mujahid Mubarak Ali. What followed was another period of uncertainty, as Nusrat found himself in the unenviable position of being the junior-most qawwal in a crowded field of established musicians including Aziz Mian Qawwal, Manzoor Niazi Qawwal, and the Sabri Brothers – who became the first Pakistani qawwals to perform for western audiences during their sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall in 1975.

Once again, Nusrat needed to prove himself worthy of his family’s legacy, and once again, fate brought him an opportunity. 1975 was being celebrated across Pakistan, India and the Persianate world as the 700th birth anniversary of Ameer Khusrau, the seminal poet, musician and Sufi. The centerpiece of the celebrations was to be a concert, held at Liaquat Auditorium in Rawalpindi, featuring three representative Qawwali parties of Pakistan. Nusrat, being the youngest, would open the concert, followed by Manzoor Niazi Qawwal and Party, while the Sabri Brothers would be the headliners, ending the concert.

When the playlists were being decided, Nusrat had to choose from the items that the other two parties hadn’t already called dibs on. He chose two unique compositions from his family’s repertoire, plus a popular composition attributed to Ameer Khusrau that the other two parties had decided not to sing. What happened next is the stuff of legend, and an important milestone in Nusrat’s ‘superhero origin story’. Nusrat’s performance was so unique, so electrifying, that chief guests including the film star Muhammad Ali, the playwright Kamal Ahmed Rizvi and the poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz rose from the audience and sat down next to the young qawwal on stage. The audience was in raptures, the senior parties’ performances were overshadowed by the young qawwal and his party, and a star was born.

There was no turning back for Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and his party after 1975, and they spent the next five years touring Pakistan, establishing their position as one of the leading Qawwal parties of the country, and releasing their first albums on the Oriental Star Agencies and EMI Pakistan labels. International stardom wasn’t far behind, with Nusrat undertaking the first of his many international tours in 1979, heading to the UK for a series of shows promoted by the UK based label Oriental Star Agencies.

A recording of one of Nusrat’s performances in Birmingham in 1979 that reached the ears of legendary actor / director Raj Kapoor. Raj Kapoor had been an admirer of Fateh Ali & Mubarak Ali Khan in the years preceding partition, and impressed by the young qawwal, he asked his friend, the Pakistani film star Muhammad Ali to invite Nusrat and his party to Bombay, to perform at the Sangeet ceremony during the wedding festivities of Raj Kapoor’s son Rishi Kapoor. This was Nusrat’s first trip to India, and he made full use of it by enthralling audiences comprising of the crème de la crème of the Bollywood film industry, releasing his first record in India, and finally paying his respects at the shrine of Hazrat Moinuddin Chishti (RA) at Ajmer Sharif, where fifteen years earlier, his ascension to the peak of Qawwali was first foretold. Even though Nusrat had never visited the shrine in his life, he instinctively made his way through the corridors of the shrine, found the place he had seen in his dream years ago, and began singing.

By the mid-1980s, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was a major recording and touring artist in Pakistan and in the diaspora touring circuit in the UK. He was performing regularly on Pakistan Television and had made his first recordings for the BBC. He had perfected his unique style of complex staccato sargams, soaring taans and intricate compositions, and was ready to truly break out onto the international music stage.

That opportunity arrived in 1985, when Nusrat and his party were invited to perform at the July 1985 edition of Peter Gabriel’s annual WOMAD festival at Mersea Island, Essex. Sharing the bill with an eclectic list of performers, Nusrat and his party performed at the midnight slot, over the next hour and a half, they presented a selection of some of their most popular qawwalis, including the now immortal compositions “Allah Hoo”, “Haq Ali Ali” and “Shahbaz Qalandar”. Even though the recordings from that session wouldn’t see the light of day for another 34 years, the legend of Nusrat and his electrifying qawwali stylings was well and truly established.

The succeeding years saw Nusrat and Peter Gabriel collaborating for the soundtrack to Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ and Michael Mann’s Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers – although Nusrat wasn’t too pleased at the makers of the latter film for using his alaap during a scene of intense violence. Nusrat’s forays into Hollywood continued in the mid nineties with his contributions to the soundtrack of Tim Robbins’ Dead Man Walking. One of his final collaborations was with the producer Rick Rubin, whose American Recordings label had earlier released critically and commercially successful, career-reviving albums by Johnny Cash and Donovan. Nusrat signed a contract with him in 1997 and recorded an initial series of performances, which would comprise the first of a four-album project. Unfortunately, these recordings with Rubin would prove to be some of the final music Nusrat would record. He died a few months after signing with Rubin, and the eight finished recordings were released four years after his death as the brilliant double album The Final Studio Recordings.

When Nusrat passed away in 1997, the outpouring of love and grief seen at his funeral was repeated at his chehlum, where as per his wishes, Nusrat’s nephew Rahat Fateh Ali Khan wore the ‘dastaar’ as Nusrat’s chosen successor. In the decades after his death, Nusrat’s legend has remained undimmed, with a whole new generation discovering and rediscovering his performances via YouTube and Spotify, as well as the countless bootleg and official releases of his music.

Just when one had thought that the well of Nusrat’s original recordings had been exhausted, comes the news of Chain of Light. It’s especially exciting news for me because, like the protagonist of Farjad Nabi’s wonderfully quirky 1997 film Nusrat Has Left the Building…But When?, my favorite Nusrat era is the pre-1990, pre-fusion, pre Mustt Mustt Nusrat, when he was transitioning from his legendary OG qawwal party (including the wonderful Mujahid Mubarak Al Khan, Atta Fareed and Maqsood Hussain on vocals) to his much more compact 1990s party. The recordings on the album include renditions of two of my favorite Nusrat pieces, plus a manqabat that has never been released before. Sandwiched between the releases Shahen Shah and the first of his collaborations with Michael Brook, 1990’s Mustt Mustt, the recordings on Chain of Light find Nusrat and his party at one of the many high points in their creative journey. The musical adventures and forays into more non-traditional performance of the mid-nineties are in the future at this point. What we will get to hear on the album is a type-specimen of a traditional Pakistani Qawwali party, led by a supremely gifted, intensely driven, divinely inspired young musician, carrying the legacy of six centuries on his shoulders while getting ready to forge ahead on new, unexplored paths in the years ahead.

If the global anticipation and excitement elicited by the announcement of Chain of Light is an indication, there will be endless poring over the performances, fresh waves of adulation and acclaim, and perhaps a whole new generation of listeners who will be acquainted with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. It is a testament to Nusrat’s training and talent, his single-minded determination in the face of adversity, and the divine gift that eludes all but the greatest artists, that twenty-seven years after his death, the phenomenon of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s immense talent still refuses to see a single day of ‘zawaal’.

I love this piece, mashallah! (one small thing, Michael Mann was not involved with 'Natural Born Killers', it was directed by Oliver Stone)

Musab, its amazing. Pls keep going.