Sampling as a Bridge

Guest contributor Shahmir writes about how sampling as a method of production has forged a transcendental connection between music from the subcontinent and the West.

Film music is one of the most ubiquitous genres across the subcontinent. Not to be confused with a film score, film music is conventionally defined as any song with a vocalist that appears during a film. Such music has been ever-present in Bollywood & Lollywood films since as early as 1931; ‘Indrasabha’ (1932) went to the extent of including nearly 69 songs during its 3 and a half hour runtime.1 The genre has produced some of the biggest stars in the world including Lata Mangeshkar, the most recorded artist in history. While such facts are well-known, a crucial aspect that has started to go unnoticed is the thriving globalization in the genre that blossomed in the 1970s and continued after that. While it can arguably be said that most film music before the 70s tended to gravitate towards folk instrumentals indigenous to multiple regions across India & Pakistan, film music in later years could also be characterized as the subcontinent’s answer to globalization. What I mean by this specifically is an incorporation of important musical trends in the West while maintaining the roots of local folk instrumentation. While there were many genres that were easternized by the film music industry including rock & funk2, I will be focusing on disco music, which had taken the West by storm in the 70s and led to the birth of multiple genres after it, including house music.

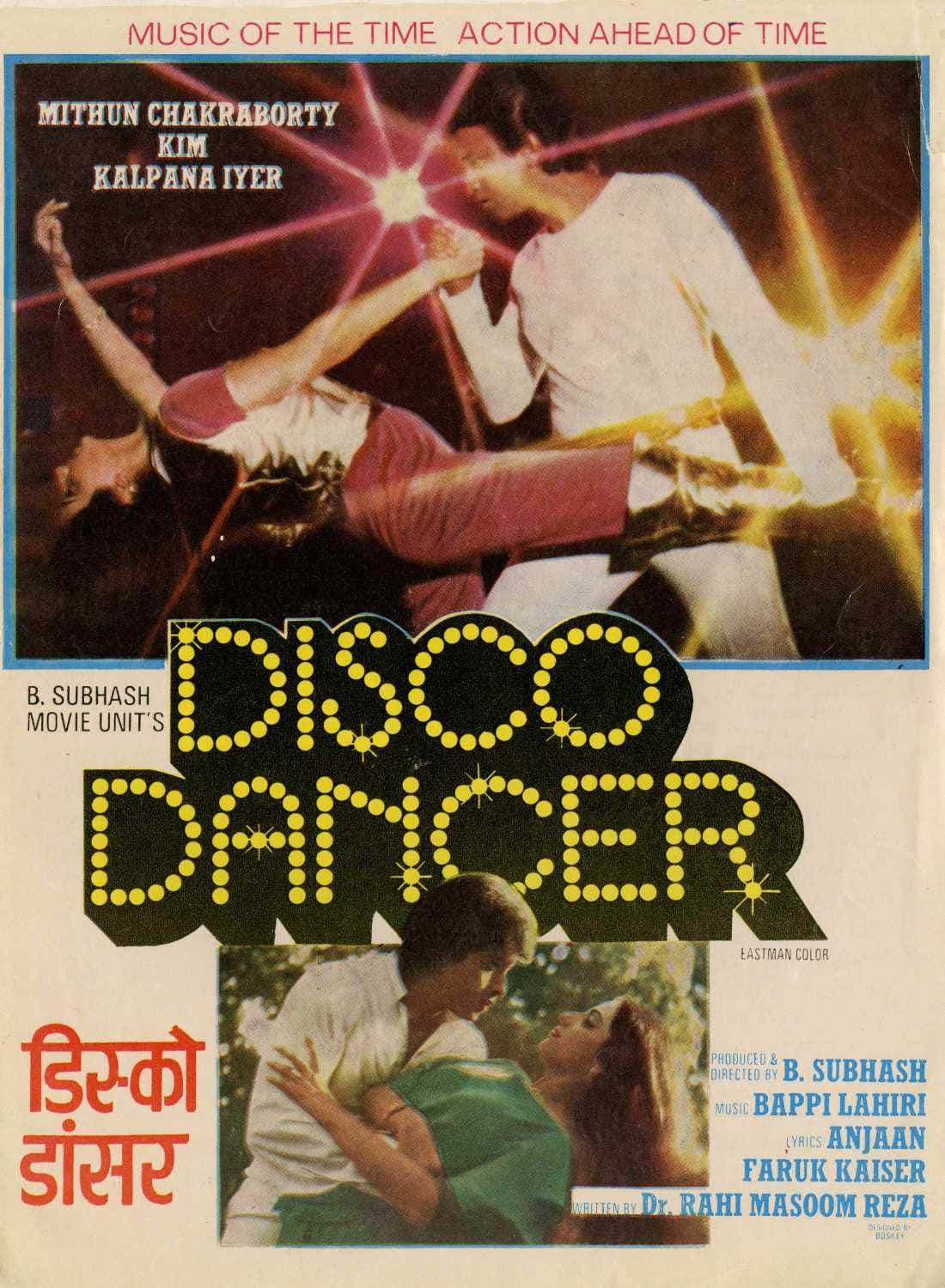

Understanding disco’s ability to act as a visceral and immediate call to the dance floor, helps us understand the subcontinent’s affinity towards it. Most film music was accompanied by choreographed dances or spectacles that were able to subvert the taboo of dancing freely or openly, which is, to an extent, still ever present today. Nevertheless, disco planted its roots in the region and innovators like Bappi Lahiri & Muhammad Ashraf incorporated the sound into what they had been working with to produce a hybrid that was at the same time novel but also recognizable. Bappi Lahiri is perhaps one of the most recognized musicians from Bollywood. His musical aesthetic felt true to a shifting world as well as the culture he came from. Quite similarly, Muhammad Ashraf had garnered huge success in the Lollywood industry for his unique sensibilities which led him to work with the likes of Noor Jehan, Nahid Akhtar, Ahmed Rushdi & Nayyara Noor. In his lifetime he composed nearly 2000 songs for over 400 films.3

To see some examples of how disco was brought into the fold of film music, we can examine Bappi Lahiri’s composition ‘Raat Baaki’ from the film Namak Halaal (1982). The bass synth line that starts the entire tune is foretelling of its intention and direction. More interestingly however, if one were to put it side by side with perhaps one of Giorgo Moroder’s most famous works, you could see where the inspiration stemmed from. Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ (1977) is perhaps one of the most popular disco songs that came out of the United States. Its genius still lives on today (it was recently sampled in Beyonce’s ‘Summer Renaissance’). Putting the two songs together, helps us understand how well the sound of disco was taken by artists like Bappi Lahiri and adapted to the setup and structure of film music. (Here’s a comparison of the two songs, side by side). This is just one example of how disco trends had started to become more popular in the late 70s and 80s, leading to some of the most recognizable film music with disco themes including Nazia Hassan’s ‘Aap Jaisa Koi’ (from the film ‘Qurbani’ (1980)), a song whose appeal/popularity endures to this day. Other artists that forayed into disco include Noor Jehan (‘Disco Dildar Mere’), Nahid Akhtar (‘Disco Deewani Mera Naam’), Tafo Brothers (the folky-disco ‘Happy New Year’ w/Noor Jehan) & R.D.Burman (‘Jane Kaise Kab Kahan’). As the incorporation of disco, along with other genres such as rock & funk, and film music started to get more frequent, the popularity of both genres started to grow in the region. This fact coupled with a booming film industry (at one point Bollywood was producing twice the amount of films that Hollywood was) are just some of the factors that helped popularize subcontinental film music into the giant it is today.

The growing position of subcontinental film music attracted the attention of ‘crate-diggers’ in the US. To understand the activity of crate-digging, imagine yourself in a record store, digging through boxes upon boxes of vinyl records across genres, time periods and cultures. You could go from a Nigerian rock record to the soundtrack of ‘Teesri Manzil’ from R.D.Burman. Crate-digging is part and parcel of many a musician’s work but it manifested in a very specific way for musicians in hip-hop. Amongst many other things, one of hip-hop’s foundations was built on crate digging and sampling - an art whereby producers were able to take sections or pieces of music from their childhood to create enduring songs such as “Hypnotize” (samples Herb Alpert’s ‘Rise’), “Shook Ones Pt.II” (samples Herbie Hancock’s ‘Jessica’) and many more. Even the first hip-hop song to be released was built on a sample: Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” samples the bassline from Chic’s “Good Times”.4

To understand why sampling was such an attractive method of music production entails, firstly, understanding the economics of music production. When hip-hop was in its early stages, the U.S recording industry was such that becoming a musician was a tough road to take. Artists had to record expensive demo tapes and have enough social capital to get the demo to record label executives. However, an alternative to that appeared through sampling, where a producer simply needed to take a record (which was usually a record that the producer’s parents or friends parents had as part of their record collection) and a sampler-sequencer (conventionally an AKAI MPC 3000). Relative to the equipment required to record demos with multiple high-end instruments, the sample-sequencer was a much more economical way of getting one’s music out there. But to reduce such an activity to just economics would be a simplistic exercise - sampling was a way to connect with a rich lineage of soul, blues, jazz & disco music (genres that were soundtracks for multiple generations) and to recontextualize sounds to create a new meaning for a newer generation.

To sample effectively, many producers spent hours upon hours digging through crates in local record stores, patiently listening through hundreds of songs in search of a perfect melodic loop or a perfect drum break ; listening intently was as important an exercise as was producing. This activity helped popularize musicians who were able to take segments of music from multiple genres and loop or chop them to create new melodies & provide a new context to such history. Sampling was a gateway to multiple possibilities, some of which included connecting with the past & securing a better future. Slowly and gradually however, crate-digging’s purpose started evolving from just a tool of connection to a way of exploring world history through a new lens. This was just one of the dominoes that ended up in Madlib’s music coming to India.

Madlib & J Dilla are some of the most well renowned producers to have ever graced the hip-hop world. Madlib was a producer who hailed from Oxnard, California and was born into a family of musicians, through which he received a lot of exposure to multiple genres that allowed his aesthetic and musical sense to develop very early on, which eventually led him to take up beatmaking. Madlib’s unique production style has helped him create classic records with the likes of MF DOOM, Kendrick Lamar, Kanye West & many more. J Dilla was a Detroit native, who, akin to Madlib, was raised by a family of musicians and became a maestro of the sample-sequencer AKAI MPC quite early on. J Dilla’s production style has not only had an influence on hip-hop, but in the way jazz musicians played thereafter (documented quite well in the new book by Dan Charnas on Dilla’s life & legacy). Dilla & Madlib’s production can be characterized by unlikely grooves and melodies but most of all with a sense of discovery. No sample was out of bounds and that led them on paths across the world.

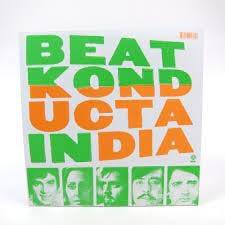

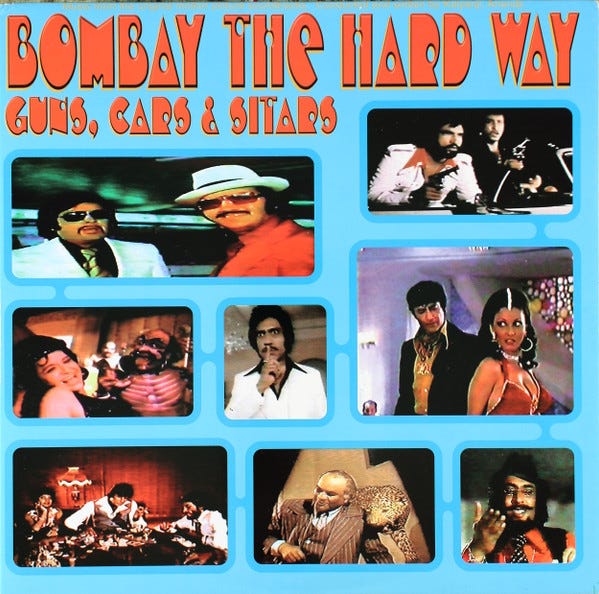

One such path led Madlib to delve into Bollywood and film music in particular. He applied his sampling technique to songs by the likes of Lata Mangeshkar, R.D.Burman & Bappi Lahiri. The resulting beats, interspersed with dialogues from Bollywood films, helped create the ‘Beat Konducta Vol 3 & 4: In India’ (2007) record, one of the very few albums to completely use samples from Bollywood as a guiding structure. To get a taste of the record’s ambition and sincerity, one could look at the trailer released by Stones Throw Records, a short while before the album’s official release date. The trailer shows select tracks accompanied by Bollywood visuals which call back to elaborate dance segments, disco flavored outfits and dialogues that pointed towards Madlib’s complete immersion into the world of film music. While Madlib’s trip to the world of Indian film music is quite revered, the precedent for such a record had already been set before by Dan the Automator who released an entire hip-hop remix album of film songs composed by the Bollywood duo Kalyanji & Anandji. The remix album was titled ‘Bombay The Hard Way - Guns, Cars & Sitars’ (1998) and operates quite similarly to Madlib’s record, with the foundations of the remixes based solely in film music but with a distinct hip-hop flavor.

While Madlib illustrated an album’s worth of film music interpretation, J Dilla recontextualized such records in ways that accompanied his songs which were mostly composed of samples from soul, jazz & funk music; their dissonance or their marriage together was entirely in the hands of Dilla. To understand this technique, we can examine Dilla’s song, from his last album (before his death) ‘Donuts’, titled ‘People’. The track starts off with a very famous Eddie Kendricks sample but then warps into a sparse percussion driven beat with a beautiful melody accompanying it, that sounds like it was made for those drums. That melody comes directly from the Asha Bhosle song ‘Mujhe Maar Dalo’. In theory, such ideas may seem a bit impossible to pull off but Dilla showed that there are ways to take seemingly dissonant ideas and meld them together to create a cohesive sound. Using such techniques, hip-hop producers have gone on to use film music samples time and time again, some of whom include: Timbaland (Jay Z’s ‘The Bounce’ samples ‘Choli Ke Peeche’), DJ Quik (Truth Hurts’ ‘Addictive’ samples Lata Mangeshkar’s ‘Thora Resham Lagta Hay’), Just Blaze (Erick Sermon’s ‘React’ sampled Asha Bhosle & Mohammed Rafi’s ‘Chandi ka Badan’) and Dilla & Madlib together (Jaylib’s ‘Champion Sound’ samples Kalyanji Anandji’s ‘Dharmatma Theme Music (Sad))’5 uniquely melding film music with hip-hop to create another unique yet recognizable sound.

While hip-hop’s exploration into Bollywood’s film music has been something special to listen to, Lollywood has always been sidelined in such an endeavor. This does not come as a surprise however. Solely in terms of production, Lollywood was not able to keep up with the amount of films being made by Bollywood yearly. Similarly, film music from the industry was not being produced at the same scale. Some of the major reasons for such a vast gap could include a lack of technical high-end infrastructure which was abundant in powerhouses of film such as Bombay & Delhi6, a series of censorship laws that came into effect in 1979 via the Motion Picture Ordinance and very few financiers for Lollywood films, after the Ordinance. These reasons, amongst many others, had contributed to a shrinking effect across an initially thriving industry: the number of cinema houses in the country went from 1300 in the 1970s to just 35 in the 1990s.7 None of this is meant to say that Lollywood was not a successful industry, but it is only to understand why Lollywood dwarfed in popularity as compared to its neighboring industry.

However, Lollywood’s rich film music industry is getting its fair due in a world where a richer conversation has opened up between film / folk music of the subcontinent and sample-based music. Not only are more producers from the West digging through troves of Bollywood & Lollywood crates, artists local to the region as well as diaspora are connecting with their musical history through sampling. A few examples would include Swet Shop Boys sampling Aziz Mian on ‘Zayn Malik’,8 the entirely Lollywood & Bollywood based album by Lapgan titled ‘Duniya Kya Hay’,9 Baalti’s music which samples sounds from Bollywood & Lollywood disco era,10 Lahori rapper Iqbal’s song ‘Charha Lo’ which samples the famous song ‘Wanga Charha Lo Kuriyo’ & UK rapper Caps' song 'Multani Kangan' which samples Noor Jehan's song of the same name.

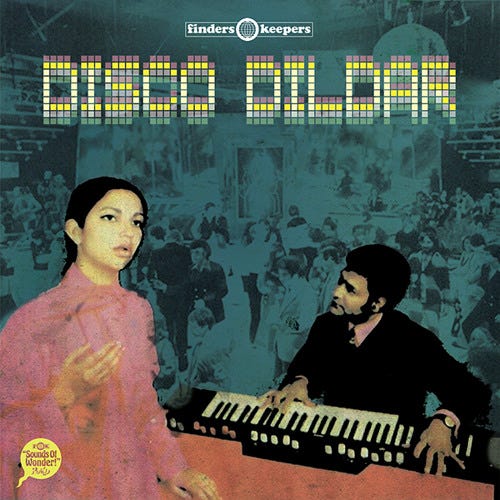

In the same vein, hip-hop has had an influence on musicians in the subcontinent as well, with the jazz ensemble Jaubi citing J Dilla as an influence on the way they started to envision Indian classical music.11 Jaubi even released a rendition of Dilla’s famous “Time: The Donut of the Heart”, to critical acclaim. Moreover, many groups have taken the initiative to preserve the rich musical history of the subcontinent: A few years ago, the record label ‘Finders Keepers’ released the ‘Disco Dildar’ compilation, highlighting disco infused songs from Lollywood.12 These are just a few of the examples that point towards an eagerness to engage with and recontextualize a rich history through new musical avenues, many of which I have not mentioned here but exist in full-force.

All of what I have talked about above can neatly be summed up by a musical mission statement once spoken by John Coltrane, highlighting the meeting of the past, present & future, in whatever way it may be accomplished: “I start in the middle of the sentence and move in both directions at once”.

To find more of Shahmir’s writing, visit his Substack.